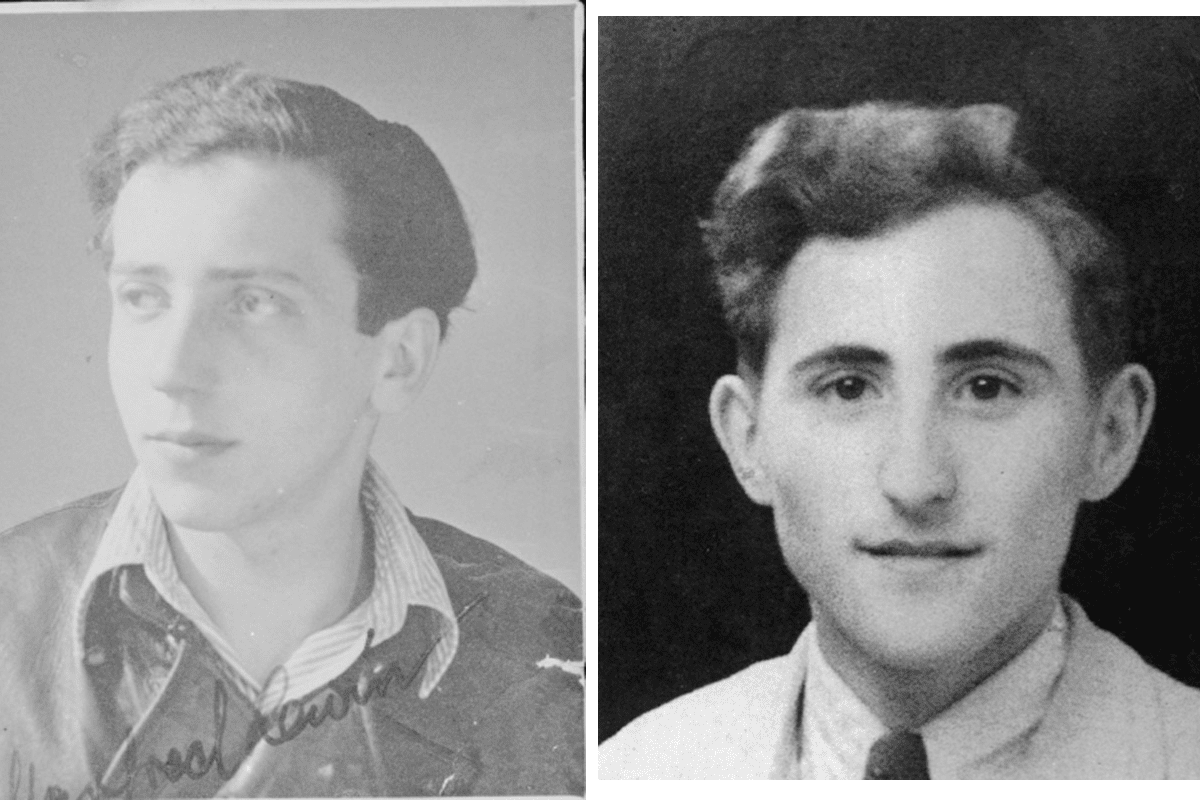

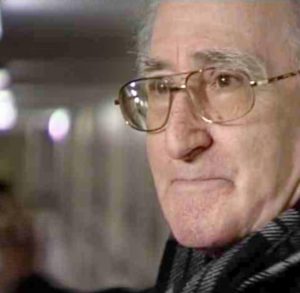

There are not many people in history as cool as Gad Beck, a gay Jewish hero in Nazi Berlin. Beck was the child of a Jewish father and a Christian mother. This kind of thing was relatively common in early 20th century Berlin. It was also the kind of thing that drove the Nazis wild, but paradoxically, it also protected Beck, his sister, and even his father, all of whom survived the war. Beck’s Christian relatives, it must be said, were never turned by the Nazis and helped protect Beck’s family too, to the extent of their power: at least they helped feed them and tried to hide them when it was necessary. The increasing separation of Jews from the rest of society made Beck feel very attached to his Jewish identity, however. He insisted, against his parents’ will, on going to a Jewish high school. He had a long series of Jewish boyfriends. And ultimately, became a leader of the anti Nazi resistance in Berlin, serving as the lynchpin of a system that kept many of the last surviving Jews in the city hidden, fed, and alive.

This was of course a very risky thing to be doing, and the story of his wartime years is full of horrible events—friends arrested, tortured, murdered—and astonishing escapes. Probably the coolest, and saddest Beck story—the one that makes him famous in Germany—occurred in 1942, when his great love, a boy called Manfred Lewin was arrested, along with his family, for deportation to the East. Beck was half-crazy with fear and grief, and he ran to the factory where Manfred had been doing forced labor, to ask his boss for help. Obviously, the boy had guts, eh? But he also knew the landscape of his culture: normal people were not necessarily Nazis, and the boss was happy to help. His son was in the Hitlerjugend, and his uniform was hanging on a hook in the office, so he told Beck to put it on and see if he could do something to save Lewin. And he did—temporarily. He went to the prison where they were being held, asked to see the commandant, and convinced him that Lewin had failed to leave certain keys that his boss needed. In short, he managed to walk out of the prison with Lewin in tow! But here is the kicker. In 1942, people didn’t yet know about extermination camps. So after a couple of minutes, Lewin said he couldn’t do it. He couldn’t let his parents be deported to a ghetto in Poland without him to help them. And he went back (I know, your heart is breaking) never to be seen again….

But that is of course only one of the hair-raising things that happened to Beck during the war. Eventually, the Gestapo found out about his organization and arrested him and a later boyfriend, Zwi Abiram. They were interrogated by the top men in the Gestapo, and Abiram was beaten severely (not for the first time, since he had been arrested before). In fact, they may have used beating Abraham as a method of breaking Beck, since he could hear Abiram’s shouts from the next room. But Beck was too canny for them. He kept up an elaborate system of lies, and they never managed to find any of the 63 Jews he was protecting. And for some reason, they didn’t torture or kill him. Maybe this was because he had information they wanted, or perhaps it was just very close to the end of the war, and they didn’t want to kill someone who by then was famous. It may also have helped that Beck recognized one of the Gestapo officials as an old customer of his father’s cigarette business. He and his sister had used to bring cigarettes to his newspaper stand, and the man and his wife had used to kiss them and give them candy! In a gap in the interrogation, Beck spoke to him about it—and somehow that too might have helped protect him.

Eventually, in any case—after being pulled out of the rubble of the prison after a bombing raid—Beck and Abiram were the last people left in a basement cell in an abandoned Gestapo prison, as the Russians closed in on East Berlin. The story has a dramatic end. A Russian soldier came into their cell, saw them, and reached into his pocket, bringing out not a revolver, as they thought he would, but a card with the question, in German, “is there someone here called Gad Beck?” And when Beck indicated that it was him, the soldier said to them, in Yiddish, “Brieder, ihr seyd frei” (brothers, you are free). Pretty amazing.

Beck and his family emigrated to Israel, but eventually, he came back to Berlin, where he was an important person and only died in 2010. His wartime autobiography, An Underground Life: memoirs of a gay Jew in Nazi Berlin, is a wonderful book: it gives you an inside view of what it was like in Nazi Berlin—including several major events at which Beck was present—and while it is of course truly hair-raising, it is also a very charming book, because of Beck’s delightful narrative style. It is typical that he calls himself a gay Jew, not a gay Jewish hero—though he certainly was one.

There is something much sadder that you can see if you are in Berlin: the plaque seen in the above image. This is something I just happened to find in Berlin this year, and it brings the whole story, or indeed the whole story of the persecution of the Jews, to life. Over the last 27 years, the artist Gunter Demnig has placed thousands of these plaques throughout Europe, on the sidewalk in front of the house of someone who was murdered by the Nazis. They are slightly raised and called Stolpersteine, “stumbling blocks.” Today there are 70,000 of them. Well…this year, when I was in Berlin for New Year’s, I happened upon the plaque for Beck’s great love Manfred, right in the old Jewish quarter in Berlin, around the corner from the Hackescher Markt.

Interested in learning more about our gay Jewish hero? About gay Berlin, Nazi Berlin, and communist Berlin? Come on Oscar Wilde Tours gay history and art tour of Berlin and Amsterdam, July 25-August 1. We will be there for Berlin’s amazing Pride celebration, and we will celebrate with a ceremony at Lewin’s plaque…