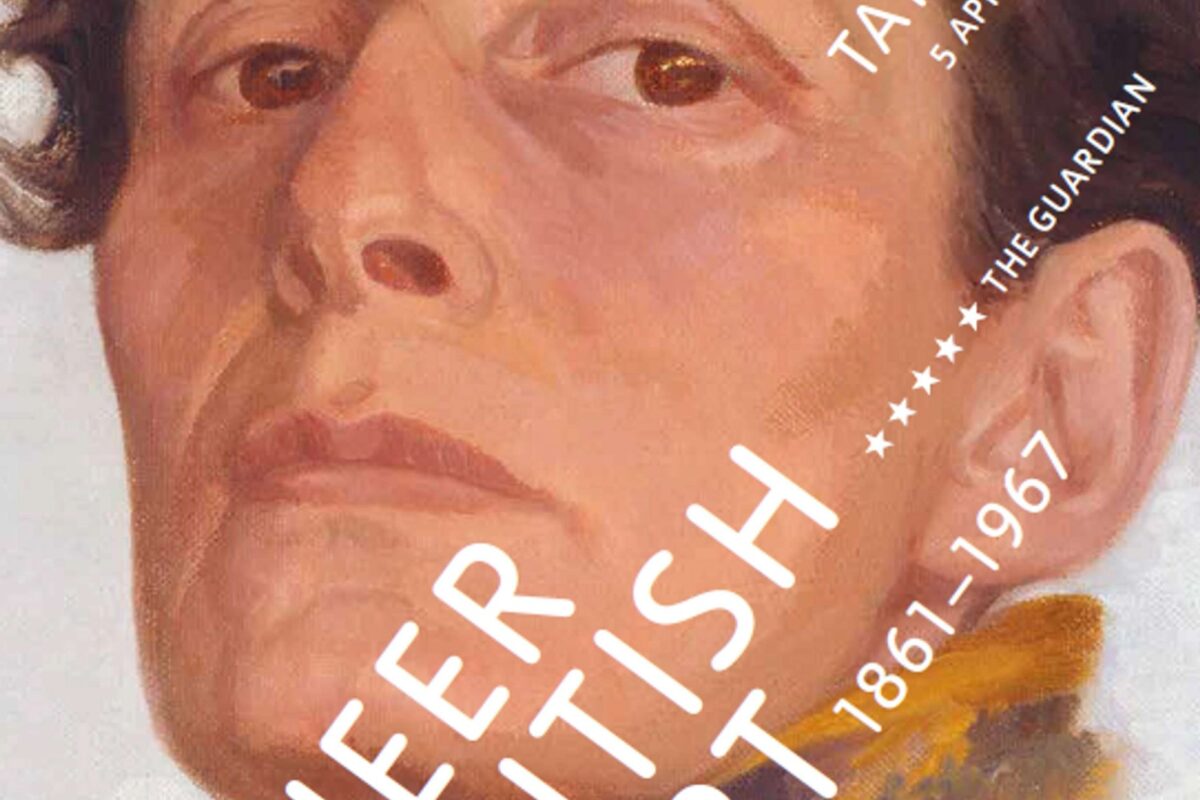

In a little over 100 years, between 1861 and 1967, Britain went from punishing male homosexuality with the death penalty to decriminalisation across the vast majority of the country. That may seem like a glacial pace but when we consider the World Health Organisation didn’t officially declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder until 1992, the UK seems ahead of its time. One of the easiest ways to trace the societal and legal shift in attitudes towards sexuality that took place in the UK at this time is to look at the artistic output of the nation. To see how British society went from treating artists like Oscar Wilde and Simeon Solomon as criminals, whose careers were both ruined by ‘gross indecency’ trials, to accepting and embracing artists like David Hockney and Francis Bacon as national heroes is a fascinating journey, and one on which we can all travel thanks to the work of the Tate gallery in London.

In 2017, to coincide with the 50 year anniversary of a landmark achievement for gay rights in Britain, the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales, the Tate put on an incredible exhibition the likes of which had not been attempted before nor since. Curated by Clare Barlow, the exhibition Queer British Art 1861–1967 took as its scope the contributions made to art history by queer British artists. Drawing on the Tate’s impressive collection, as well as loans from other institutions and private individuals from across the world, the exhibition brought together more art by queer artists than had ever been seen in one place before. There were names recognisable to all (Oscar Wilde, Noel Coward, Virginia Woolf) as well as names whose reputation had decidedly diminished in the intervening decades (Gluck, Claude Cahun, Michael Field). Not only a celebration of artistic achievement in the face of persecution, the exhibition served as an excavation of incredible stories and people, whose fascinating lives and legacies were often overlooked or dismissed by a conformist society.

Of all the artworks and artists on display it would be impossible do justice (in a literal and metaphorical sense) to any of them in the manner in which they deserve, at least not in one blog post or one Zoom talk, but here I shall highlight three—hopefully giving you a sense of what a wild, wonderful and dazzling world queer British art became, and I will start with something that isn’t actually art at all.

Oscar Wilde

You’d be forgiven for wanting to push past the story of Oscar Wilde. His story has become so familiar to us that it seems like there’s nothing new to be gained from going over it. This was something the curator of the Queer British Art, Clare Barlow, was all too conscious of. Ingeniously, the exhibition presented an object that brought Wilde’s demise into a fresh

and heart-wrenching perspective. Alongside the Pennington Portrait of Wilde, the very image of a confident young man on the cusp of fame, stood Wilde’s cell door from Reading Gaol. I remember seeing this in the gallery myself and succumbing to Wilde’s story as never before. The triumph and the tragedy was at once summed up by two objects seen for the first time side-by-side. One was brought face-to-face with Wilde’s misery: the two years that he spent behind this oppressively metal door laden with locks, in a new form of punishment that would go on to be known as solitary confinement. From behind this door Wilde wrote De Profundis, a letter to the lover that put him behind this door, Lord Alfred Douglas. Allowed one piece of paper a day, which were taken from him at the end of each day, Wilde wrote one of the most profound letters in all of English literature. At the end of his sentence Wilde was allowed to take with him all the pages he had written. He never edited them after leaving prison and never saw them published in his lifetime. Indeed, it was not until 62 years after his death that the letter was published in full.

Dora Carrington

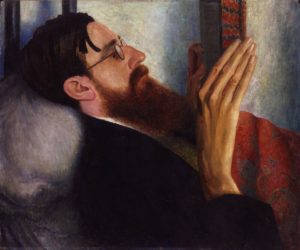

After Oscar Wilde, the next stop along the journey of queer British art would for most people be the Bloomsbury Set. Known as a bohemian group of privileged individuals who eschewed virtually everything traditional, the Bloomsbury Set defined the style of ‘modern’ Britain in the early 20th century. Despite being one of the group’s most talented painters, Dora Carrington (1893–1932) was completely overlooked for many decades after her death. To me, Carrington (as she was known by the group) sums up the Bloomsbury Set just by being herself. She was a brilliant and uncompromising artist, an emblem of the modern lifestyle, and she lived a life that oscillated between privilege and tragedy. Carrington went to the notoriously liberal Slade School of Art in London in 1910. She was top of her class but seemingly never converted the adulation she received into confidence.

Indeed at one point she even stopped signing her name to her paintings. She is chiefly remembered now for her relationship (or lack thereof) with Lytton Strachey, one of the preeminent writers of the Bloomsbury Set. Lytton was a homosexual and did not reciprocate Carrington’s affection, but true to Bloomsburian form, they lived together for much of their lives in an unconventional arrangement. Such was the intensity of Carrington’s feelings for Strachey that when Strachey became infatuated with a young man named Ralph Partridge, Carrington married him to keep Strachey close by, forming a ménage à trois. Tragically for Carrington, Strachey died prematurely from cancer, leaving her utterly bereft. Just a few weeks later, she donned Strachey’s dressing gown, walked into his bedroom and turned a gun on herself. Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary “Glad to be alive and sorry for the dead: can’t think why Carrington killed herself and put an end to all this.” An oddly brusque remark, given that Woolf followed Carrington’s example and killed herself just nine years later.

David Hockney

Plenty of queer artists, writers and performers made names for themselves between Dora Carrington’s death and the 1960s, but none changed the way queer lives were viewed in art more than David Hockney. If you are not British, it is hard to sum up what a national legend David Hockney is. He is the emblem of a British artist, one whose work has never, never, gone out of fashion in his 70+ years of making art (and counting!). Who would be his American counterpart, the elder statesman of queer American art? Jasper Johns? Too abstract. Robert Rauschenberg? Too avant-garde and far too dead! If you have suggestions, please Tweet us!

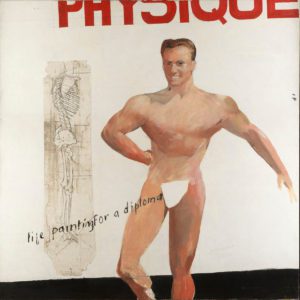

It is only when you reach Hockney that you find an artist who did not hide his sexuality in any way, someone who made his works completely transparent in meaning. He called his early work ‘homosexual propaganda’ and has said “I would always defend my life, as it were, and what I was up to. I would certainly defend my way of living”. Before Hockney, queer art was laced with shame, guilt, secrecy or coded intellectual references to Ancient

Greece. Hockney’s art was and is self-celebrating. All of this is evident from the get-go with his work Life Painting for a Diploma (1962). Hockney only painted this painting to satisfy the life study assessment criteria at the Royal College of Art. Cheekily, the image of a bronzed and muscled adonis is lifted from The Young Phsyique, a magazine that functioned as thinly-veiled gay pornography. In Hockney’s words, his painting is “mocking their idea of being objective about a nude in front of you when really your feelings must be affected”. And that was Hockney’s revolutionary moment. What was he interested in? Boys! So what did he paint? Boys! And without any shame whatsoever. No pretence, no codes, no mythology, just pure, unadulterated admiration for the male form by a male artist. Considering this was still a time when a man could be jailed for life for having sex with another man, Hockney’s work was truly bold, irrepressibly joyful and politically pioneering. Hockney ends the exhibition with love and light, the culmination of 100 years of movement towards gay rights and queer liberation.

If you want to know more about those 100 years, and more about the Tate’s incredible exhibition on Queer British Art, all you need to do is sign up for my Zoom talk all about it! There really is nowt as queer as British art.