At the end of this very real annus terribilis, I want to say a few words to you, our loyal readers and attendees. Above all, thanks! Thanks for keeping Oscar Wilde Tours alive by reading our blog, attending our Zoom tours, watching our YouTube videos, contributing to our fundraisers—in short, for being a fabulously loyal community. When the pandemic hit the US, in March, it seemed likely to kill the company completely. Who would have thought that 9 months later, as the pandemic continued to rage, we would be putting on our 28th Zoom tour, with audiences regularly over 100, and have gathered over 28,000 views for our videos? It’s been a hard year, but ours is a tiny, flourishing corner. And we have a lot more coming after the holidays! Want to find out more?

Queer British Art

In a little over 100 years, between 1861 and 1967, Britain went from punishing male homosexuality with the death penalty to decriminalisation across the vast majority of the country. That may seem like a glacial pace but when we consider the World Health Organisation didn’t officially declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder until 1992, the UK seems ahead of its time. One of the easiest ways to trace the societal and legal shift in attitudes towards sexuality that took place in the UK at this time is to look at the artistic output of the nation. To see how British society went from treating artists like Oscar Wilde and Simeon Solomon as criminals, whose careers were both ruined by ‘gross indecency’ trials, to accepting and embracing artists like David Hockney and Francis Bacon as national heroes is a fascinating journey, and one on which we can all travel thanks to the work of the Tate gallery in London.

LGBTQ England and its Queerest Stately Homes

One of the great things about England is its grand, historic houses, what the British call “stately homes.” Today’s post is about two castles with an LGBTQ past. And who better to write about LGBTQ England and its Queerest Stately Homes than Nick Collinson and Dan Vo? Nick is the founder of the LGBTQ working group at English Heritage, and Dan, who developed the well-known LGBTQ tours at the Victoria and Albert Museum and is now project manager of the Queer Heritage and Collections Network, a partnership of the National Trust, English Heritage, Historic England, and Historic Royal Palaces.

Nick: When I decided to form our group at English Heritage, one of the names that was suggested was ‘Stately Homos’. We decided against that name firstly because we are custodians of many other sites besides stately homes (Stonehenge, Hadrian’s Wall, Dover Castle etc…) and also we wanted to include all parts of LGBTQ England and its spectrum of genders and sexualities.

But it got me to thinking about all those homos who lived in stately homes, and all the debauchery that must have gone on in the billiard rooms, bedchambers, back stairs and butteries. Many of these homes are hundreds of years old, and the sheer number of staff they employed means that a significant number must have been interested in a bit of same-sex screwing from time to time. Unfortunately, due to the way history has been recorded, it is incredibly difficult to uncover stories about those ‘below stairs’ but the sexual goings-on of some of the more illustrious inhabitants have been recorded for posterity…

Madresfield Court: Brideshead and the Beauchamp scandal

Madresfield is one of those fairytale gothic erections, set in parkland beneath the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire. It has been in the Lygon family since the 1100’s – longer than any other dwelling in the UK, apart

Madresfield

from a few owned by the Royal Family.

The Lygons are famous in the LGBTQ community. Well, not under their real name—but they are the model for the Flyte family in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited: Sebastian, the narrator/Waugh’s big college crush was called Hugh Lygon in real life. But while the novel focuses on Sebastian’s *father’s* scandal, Waugh never mentions what the real scandal was about.

Well….William Lygon, 7th Lord Beauchamp, inherited the house in the late 1800s. He was holder of many high

Lord Beauchamp

public offices, including Governor of New South Wales in Australia. He suffered a spectacular fall from grace when he was ‘outed’ to the King by his bitter and twisted brother-in-law Hugh “Bend’or” Grosvenor, Duke of Westminster (probably because he had such a gay nickname himself!). We know Beauchamp had a penchant for good looking servants, as detailed by this tongue-in-cheek article in the Australian Star:

The most striking feature of the vice-regal ménage is the youthfulness of its members … Rosy cheeked footmen, clad in liveries of fawn, heavily ornamented in silver and red brocade, with many lanyards of the same hanging in festoons from their broad shoulders, [who] stood in the doorway, and bowed as we passed in … Lord Beauchamp deserves great credit for his taste in footmen.

While he was hosting a dinner in the medieval Great Hall at Madresfield, one of the guests was shocked when they overheard Beauchamp saying to the handsome Butler, Bradford, “Je t’adore”. The guest relayed this exchange to fellow guest Harold Nicolson (see below) in disbelief, but Nicolson, in all his bisexual wisdom, replied “Nonsense – he said ‘shut the door.’”! Always looking out for each other *wink wink nudge nudge*…

Madresfield Court is littered with little material clues to the aesthete Earl’s homosexuality, from the quartz balusters surrounding the mezzanine floor in the center of the house, to the seat covers in the library that he embroidered himself while in exile. I’m not saying that his propensity to sew and his love of shiny things is evidence enough for his being gay, but these little details add a rich timbre to the stories about him. Looking at and visiting the places where people actually lived, provide an extra dimension and tangibility to their stories. Beauchamp definitely had the Queer Eye!

Sissinghurt Castle: Queer Love Triangles in an Idyllic Garden

Dan: Great to hear Harold Nicholson would look out for a fellow indulgent queer! He was certainly one who succumbed to much temptation in his lifetime, and where better a backdrop for illicit liaisons than in a garden. I would like to conjure up in your mind a glorious and bountiful Garden of Eden, where queer sexuality was as fragrant, and flagrant, as the rich blooms. The setting is Sissinghurst Castle Garden, and it was the creation of husband and wife Harold Nicholson and author Vita Sackville-West—a couple that had a fascinatingly post-modern harmonious understanding concerning each other’s extramarital, same-sex affairs. Not that it wasn’t sometimes complicated, for example when Vita had a love affair with Harold’s sister Gwen St Aubyn. Let’s return to that shortly.

Vita called Sissinghurst her “Sleeping Beauty’s castle.” What’s remarkable is the way in which the garden was

Sissinghurst white garden

created in order to foster the many relationships that Harold and Vita had. Vita reminisced about the warm moonlit summer evenings, when love could flourish among the flowers and bushes arranged into intimate outdoor rooms and pleasant vistas. There living quarters were also divided in a similar way; the couple’s younger son Nigel (whose book Portrait of a Marriage revealed his parents’ lifestyle to the public) compared the house to a village, where everyone could live together, yet also have their own separate and private lives. Vita for instance claimed the romantic Elizabethan Tower, where she had her study, whereas Harold’s study was to be found in the South Cottage. The careful organization of the couple’s life was also seen in the movements of their lovers. Harold worked during the week in London, where he often shared his bed with a series of younger men. Vita would send her lovers, whom Harold called her béguins—infatuations—away for the weekend when Harold returned to Sissinghurst, although sometimes he arrived with another guest that his boys would dismiss as “one of Daddy’s new friends”.

Vita’s lovers included her sister-in-law Gwen St Aubyn, socialite Violet Trefusis, and most famously author Virginia Woolf, who imaginatively portrayed Vita as the gender-shifting hero/heroine of her novel Orlando. As

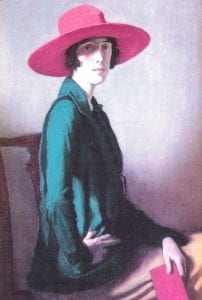

Vita in 1918 by William Strang

was said of the Bloomsbury group, Vita tended to “love in triangles”. The triangle between Vita, Harold, and Harold’s sister Gwen certainly illustrates the unique marriage arrangement between Vita and Harold. Another significant and perhaps even more complicated love triangle was the one between Vita, Violet, and Virginia. Violet fell in love with Vita while they were still teenagers, and while both married, the relationship almost broke up both marriages. Vita even interrupted Violet’s honeymoon to demand Violet sleep with her, and some accounts indicate Violet had given exclusive sexual rights to Vita alone! Harold was unusually perturbed and put his foot down and (having flown to France in a two-seater with Violet’s husband to recover Vita) demanded an end to the relationship. While her affair with Virginia occurred later, the ghost remained, and Virginia acknowledged this in Orlando by having Violet appear as Princess Sasha, the object of Orlando’s deepest affection.

Orlando is set in (a fictional version) of another nearby stately home Vita’s childhood and ancestral home, Knole, but it is at Sissinghurst—and especially in the garden—that one finds the essence of Vita’s (and Harold’s) amazing take on sexuality and relationships, making it one of the greatest Stately Homes in LGBTQ England.

Tilda Swinton as Orlando

Check out Nick and Dan’s tour of LGBTQ England and its queerest stately homes on Zoom, Sunday August 29, 2020.