Gay men have always been part of the American military. In an era before gay marriage or open pride, military men fell in love, formed passionate friendships and had same-sex encounters same-sex encounters. Due to social and official discrimination, though, most of their stories have gone untold. But in the case of one of the military’s founding heroes, homosexuality was always part of the story.

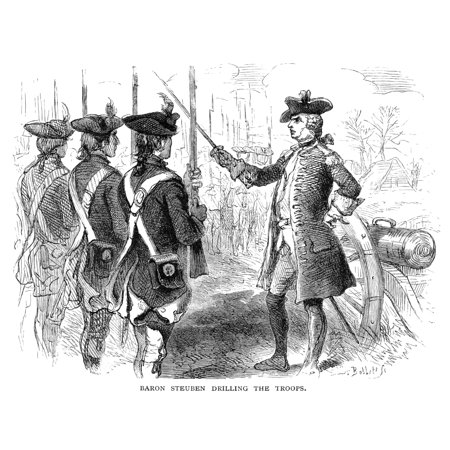

Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian military man hired by George Washington to whip the Continental Army into shape during the darkest days of the Revolutionary War, is known for his bravery and the discipline and grit he brought to the American troops. Historians also think he was homosexual—and served as an openly gay man in the military at a time when sex between men was punished as a crime.

“Though his name is little known among Americans today,”writes Erick Trickey for Smithsonian, “every U.S. soldier is indebted to von Steuben—he created America’s professional army.”

It wasn’t easy: Three years into the Revolutionary War, the army was low on discipline, morale and even food. With his strict drills, showy presence and shrewd eye for military strategy, he helped turn them into a military powerhouse.

Benjamin Franklin, who recommended von Steuben to Washington, played up his qualifications. He also downplayed rumors that the baron had been dismissed from the Prussian military for homosexuality. Von Steuben joined the military when he was 17 and had become Frederick the Great’s personal aide, but despite a seemingly promising career he was abruptly dismissed in 1763. Later in life, he wrote about an “implacable enemy” who had apparently led to his firing, but historians are unsure of the exact circumstances of the dismissal.

After being fired, von Steuben bounced from job to job. He was unimpressed by Franklin’s suggestion that he volunteer to help the American army, and tried instead to get another military job in the court at Baden. But his application was tanked when an anonymous letter accused him of having “taken familiarities” with young boys.

As historian William E. Benemann notes, there’s no historical evidence that von Steuben was a pedophile. But he was gay, and homosexuality was viewed as a criminal aberration by many of his peers. “Rather than stay and provide a defense, rather than call upon his friends…to vouch for his reputation, von Steuben chose to flee his homeland,” writes Benemann.

Franklin likely knew of the rumors and the reason that von Steuben suddenly accepted an offer he’d turned down so recently. But he didn’t see von Steuben’s private life as relevant to his military qualifications. Neither did George Washington, who knew of the accusations but welcomed von Steuben to his camp and assigned Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens—both of whom were involved in what some historians have dubbed a “romantic friendship”—as his aides.

Washington approved of von Steuben. “He appears to be much of a gentleman,” he wrote when the baron arrived at camp, “and as far as I have had an opportunity of judging, a man of military knowledge, and acquainted with the world.”

When von Steuben arrived in camp, he was appalled by the conditions the soldiers had been fighting under, and immediately set to work drilling soldiers with strict Prussian techniques. He was a strict drillmaster, but he also socialized with the troops. One of his aides, Pierre-Étienne Du Ponceau, recalls a particularly wild party given at Valley Forge. “His aides invited a number of young officers to dine at our quarters,” he wrote, “on condition that none should be admitted, that had on a whole pair of breeches.” The men dined in torn clothing and, he implied, no clothing at all.

Meanwhile, von Steuben proved himself a heroic addition to the army. As Inspector General, he taught the army more efficient fighting techniques and helped instill the discipline they so sorely needed. It worked, and the drill manual he wrote for the army is still partially in use today. The drillmaster quickly became one of Washington’s most trusted advisors, eventually serving as his chief of staff. He is now considered instrumental in helping the Americans win the Revolutionary War.

When the war ended, Baron von Steuben was granted U.S. citizenship and moved to New York with North and Walker. “We love him,” North wrote, “and he deserves it for he loves us tenderly.”

After the war, von Steuben legally adopted both men—a common practice among gay men in an age before same-sex marriage was legal. They lived together, managed his precarious finances and inherited his estate when he died in 1794. John Mulligan, who was also gay, served as von Steuben’s secretary and is thought to have had a relationship with the baron. When von Steuben died, he inherited his library and some money.

During von Steuben’s lifetime, the concept of gay marriage, gay pride or coming out was unthinkable and there was no language or open culture of homosexuality. But historical homosexual relationships were actually common.

That doesn’t mean being gay was condoned: Sodomy was a crime in colonial America. But romantic relationships between men were widely tolerated until the 19th century, and only in the early 20th century did the U.S. military begin officially discriminating against people suspected to be gay.

Von Steuben may have been one of early America’s most open LGBT figures, but he was hardly the only man whose love of other men was well known. And though he was to have helped save the American army, his contribution is largely forgotten today.